While coastal tourism is an important source of GDP in the Caribbean, it is also vulnerable to global environmental change. Sea level rise, increased severity of storms, and coral bleaching are only a few of the changes anticipated for islands in the Caribbean, and these have direct implications for coastal tourism. This, coupled with constantly changing global tourist demand and locally induced environmental change, creates uncertainty of what types of vulnerabilities will emerge and for whom.

Coasting challenges

One of the challenges for islanders facing globally induced environmental change is that their role in creating the problem seems limited. The problems and uncertainty that comes with it seem so large and external. Many islanders also do not see what they can do nor how environmental changes can affect them personally. Although coastal destinations may be limited in their contributions to mitigating climate change, they do have options to protect their island’s resilience and improve their adaptive capacity.

Most of the adaptation actions focus on creating infrastructure, such as sea walls, to protect the coast. Many tourism researchers have noted that these actions fall short of the complexity of the system. More research needs to be done on human environmental dynamics as anthropogenic influences are key when considering coastal settings where tourism occurs. Tourism, however, is not an easy setting to perform experiments, and research methods typically involve surveys, interviews, and focus groups.

Coasting simulation – researcing environmental change in coastal tourism

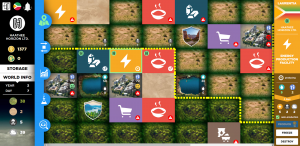

This research takes a different approach. One of the goals of this research was to develop a tool to explore the dynamic nature of environmental change in coastal tourism and emerging vulnerabilities. Using companion modelling as part of a systems approach, the Coasting game was co-developed with local stakeholders on Barbados and Curaçao.

In the game, players can take on one of four different tourism operators’ roles and make decisions on their individual operations. At the same time, they are confronted by changes to the coastal system induced by each other’s actions or external situations, such as storms and coral bleaching, and they need to decide whether and how (individually or collectively) to respond. The game looks at trade-offs among different private resource inputs, short-term versus long-term investments, and private versus public goods. As well, it explores how stakeholders respond to different changes and what their perspectives are of these emerging changes.

The Coasting simulation was played by tourism operators, government officials, NGOs, and other interested locals. One of the challenges for this simulation, and gaming in general, is getting people together. This was especially the case as this research is not part of a larger project and long-established networks had not previously existed. A second challenge was how to describe a serious gaming session to people who were unfamiliar with this method.

Changing perception of the problem

When it proved too difficult to get small groups of people together in the first case study area of Barbados, I used simulation-guided interviews to get data, help verify different parts of the game, and develop the game further. For example, I asked the tourism operators what environmental features on the board were important to them and how the particular resources determine their location. I could also go through some of the scenarios and ask how the changes would affect their decisions.

When I moved on to the second case study in Curaçao, I used the simulation-guided interview format to help interviewees give more specific information on different spatial, resource, and feedback information. Having the simulations present during the interviews made it easier to explain the idea of a simulation setting and have individuals willing to participate in gaming sessions. This helped increase the number of simulation sessions I could organise.

Through my research, I found simulations helpful for visualising environmental change and how change affects the individual as well as the system at large. Along with helping stakeholders visualise potential changes, the game sessions provided the opportunity to see what others were doing and discuss challenges with other people that they do not tend to come in contact with. This helped open up a dialogue of the issues they are experiencing and may help bridge the gap between the science-based urgency to act and the local stakeholder perception of how they can respond to uncertainty.

If you find the Coasting game interesting, browse more games on the topic in the Gamepedia, and share your experience in comments below the post!