When we think of “capital” we often associate it with money or with physical goods. But the capital has a much wider meaning – it may be human, social or natural. It’s natural capital that is the most important for the Natural Capital Project, a partnership between Stanford University and the University of Minnesota, The Nature Conservancy, and the World Wildlife Fund.

As the ecosystems can help us with regulating climate or cleaning water, The Natural Capital strives “to shine a light on the intimate connections between people and nature, and to reveal, test, and scale ways of securing the well-being of both.”.

The Natural Capital Project works in many areas, including resilience to climate and coastal hazards in Belize and development planning in British Columbia, The Bahamas, and Myanmar. All that supported by the extensive software and mapping techniques used during meetings with local administration and planners.

But as “the process of preparing spatial data, running software tools, and appropriately interpreting results can be challenging”, The Natural Capital decided to prepare a more accessible tool – a serious game.

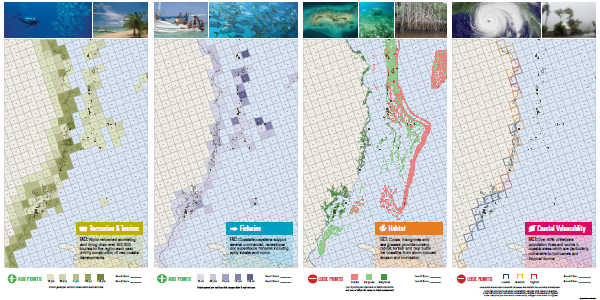

The Tradeoff! is a series of “mapping games that simply introduce concepts related to nature’s benefits to people”. With 3 versions of the game already available, Tradeoff! is a complex but easy tool which supports understanding of t coastal zone management, terrestrial/freshwater services and arctic development.

Why did the Natural Capital decide to create a new game rather than to focus on software’s development? What are the benefits of using the game, and how can it affect the attitude toward sustainable development? We discussed those and more questions with Henry Borrebach, the leader of the Natural Capital Project’s training team.

What, in your opinion, are the key elements of a serious game?

When the Natural Capital Project (NatCap) and our partners look into creating a new training game, we often have similar objectives, which tie directly to the elements of the games we develop: 1) Engage our learners in an interactive way, 2) Create ways for learners to come to key points themselves through their actions in the game, rather than through presentations or lecture, and 3) Try to simulate real-world circumstances within the game (e.g. the challenges of simplifying real-world data for various audiences, interacting with stakeholders with different values, etc.).

What do you think are advantages of game-based learning?

People learn in a lot of different ways, and teaching with games is a way to utilize different modalities simultaneously, combining, for example, visual, auditory, and experiential learning. It also gets people up and moving around (in the case of our games), and in workshops where all of the learners don’t know each other, it helps break the ice and get everyone talking to each other and talking about the concepts.

Could you briefly describe what the game(s) is about?

The Tradeoff! game series is about nature’s benefit to people, and about how development and planning decisions affect the value of those benefits.

Through the game, participants try to make decisions that strike a balance between the gains derived from things like agricultural or infrastructural development and the potential losses of natural value caused by that development. It’s also about how gathering spatially-explicit data about nature’s value can help inform better planning decisions. There are four version of Tradeoff! that cover different environments and decision contexts: 1) Best Coast Belize (coastal zone management), 2) Tradeoff! Agriculture Edition (farming, ranching, and terrestrial/freshwater ecosystem services), 3) Northland: Arctic Choices (Arctic-region development expansion), and 4) Roads to a Resilient Future (linear infrastructure and terrestrial/freshwater services).

What were/are the main challenges for the designing the games?

One of the biggest challenges we face is finding the balance between detail and abstraction. For a game to run well, we often need to simplify the circumstances, data, and decisions involved, but we’re also teaching science-based approaches and tools, so if we abstract too far away from empirical details, we’ll either lose our credibility, or fail to actually teach what we’re trying to get across in the game. Another big challenge is that, because NatCap runs trainings and workshops, and plays these games around the world, we have to build games that will not only reach audiences of very diverse technical/educational backgrounds and skillsets, but will also translate across cultures, languages, and contexts.

Are there skills needed to play the game(s)?

The Tradeoff! games have been designed to be playable by people who are completely new to the concepts entailed, but also to still be engaging for practitioners and experts in the field.

What are the most important lessons that can be learned from playing the game?

One of the most important lessons is that there are already data and tools available that can help people make better, more informed decisions, to improve the sustainability and resilience of development, spatial planning, or other similar projects. Another key takeaway is that it’s not a binary choice between development and conservation, but that there are many co-benefits and synergies to be found, and that oftentimes, sustainable solutions are win-wins for both people and nature.

Do you think that serious games can promote sustainability? If so, how?

I certainly think they can. The games that we work on at NatCap are designed to help train practitioners working around the globe learn the skills they need to do work that directly links to many aspects of sustainability, from coastal zone management and hazard mitigation, to sustainable development planning and best agricultural practices. The better we’re able to teach our learners, the more likely they’ll be able to put what they’ve learned into immediate action. For broader audiences, games can make big ideas more approachable, and can make facts that will seem tedious in non-interactive settings much more engaging. And people who are more engaged by these ideas about sustainability, I think, are much better positioned to take action in the world.

What sustainability goals can be achieved by using your games?

We’ve designed multiple games to be able to reach into different environments and planning/development decisions, so we’re certainly trying to have a wide reach in impacting sustainability goals in a variety of places. Primarily, though, I think the Tradeoff! games are about teaching both practitioners and decision-makers that we can make these sustainable and resilient decisions now—we don’t have to wait for some future technology to push toward sustainability; it’s achievable already.

One last, more personal question. If you had to choose, what would you say your three favorite serious games are?

I had a great experience playing a game with a collaborative project called Seeds of a Good Anthropocene, in which everyone had to first come up with their own seed. But then form teams and alliances to pitch imaginary projects to a panel of judges. It was a great way to learn about other cool initiatives in the world. It was great for the organizers as a way to collect a whole bunch of “seeds” for their collection all at once.

Another great game is from WWF, called Get the Grade. It combines a bunch of great elements: it’s a role-playing game, with competition and alliances at your own table, but each tables is also competing as a team against the other tables/teams in the room.

And, one more: It’s actually a kids game, but I’m a big fan of Don’t Flood the Fidgits, an online game from PBS Kids. Kids (or adults, really) have fixed budget and different options for what to build, in order to make towns for the Fidgits that will survive flooding events.

How did you like this interview? Let us know in the comment section or on our social media!