This June, two groups of NGO workers met in two distant parts of the world – Peru and Indonesia. Despite 18,000 km of ocean separating them, they shared a common goal: to help river valley communities that are vulnerable to floods. They were going to explore the ways to do that by playing a game.

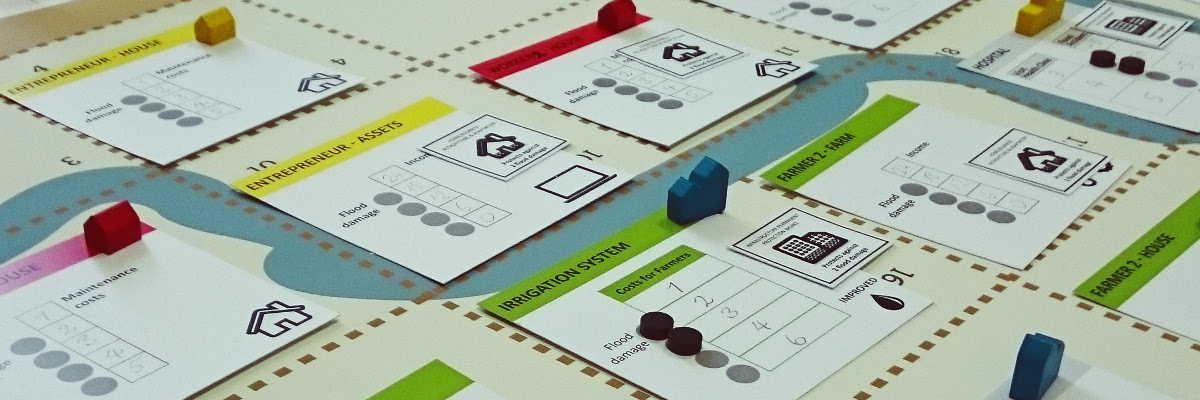

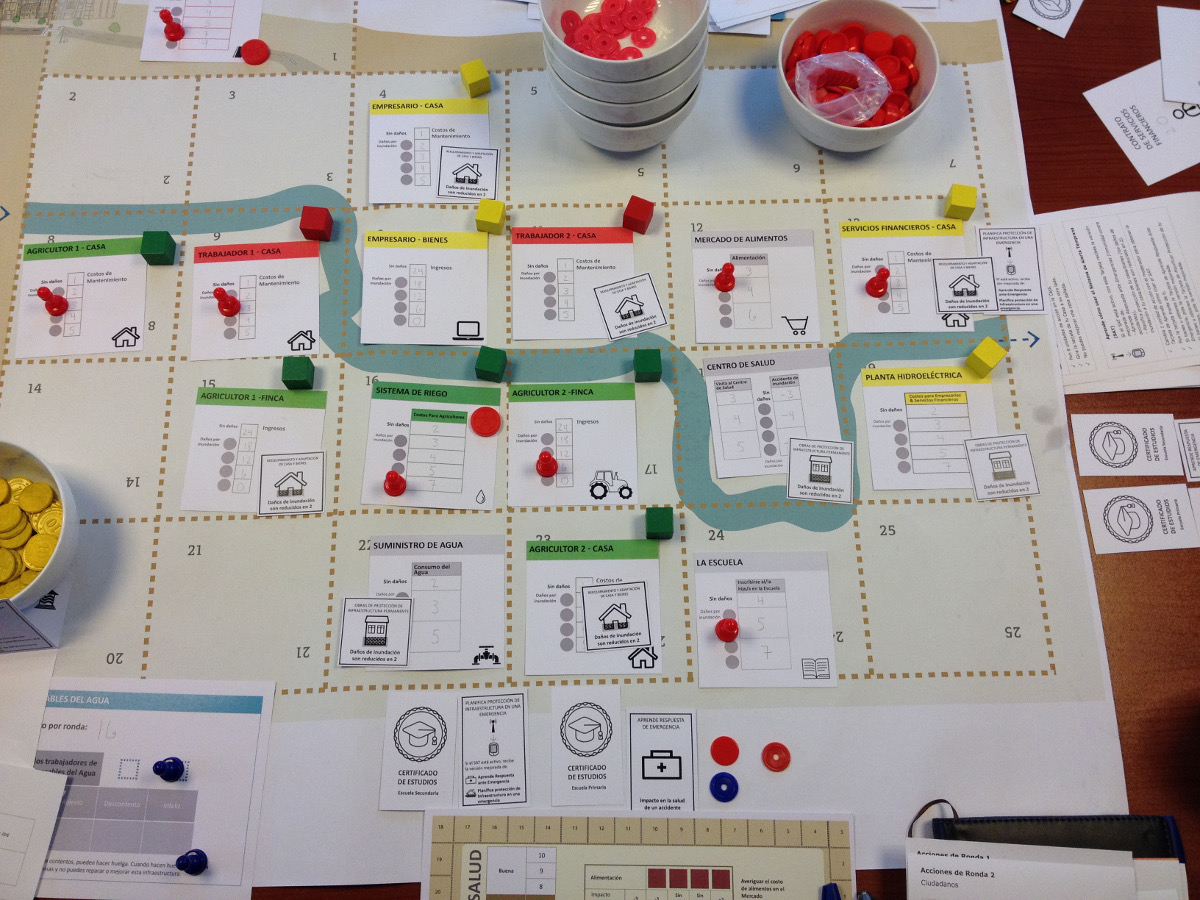

The Flood Resilience Game is a simulation that helps the flood professionals to identify policies and strategies that can make flood-prone communities more resilient.

But what does it mean, to be resilient?

There is this old fable about the oak and the reed. Both plants grew in the area exposed to wind and storms. The oak trusted in its strength, while the reed bent to the wind. Then the storm came. It broke the oak – but the reed survived. Bent but unbroken, it was able to adapt smartly to the new living conditions.

And this is what flood resilience is: the ability of a community to continue functioning and developing when struck by a flood.

The game presents the challenges that flood-prone communities in developing countries face every day. This way it creates an environment for exploring the strategies to increase flood resilience. The NGO staff who tested the game in Jakarta and Lima took roles of citizens living in a river valley (farmers, workers, entrepreneurs) and its authorities (local government and the water board). They confronted the harsh day-to-day reality. While the citizens had to find ways to provide for their families, the authorities bore the responsibility of managing the valley’s infrastructure and advancing its development.

The community in the Flood Resilience Game works as a system where all the parts are connected.

As their resources are limited, both citizens and authorities must face hard choices.

How much the residents spend on their food depends on the state of the food market. If they don’t eat properly, their health will worsen, they will be less efficient at work and in result they will earn less. They can go to the health clinic, but it costs them their hard-earned income. Their households bring them losses when flood damages them. They have children that they would like to educate, but the accessibility of education depends on the state of the local school.

Farmers suffer losses when the water supply is damaged; when the road is in a bad shape, workers have to spend more time to get to their workplaces in the distant city; entrepreneurs rely on the electronics and machines so they cannot provide their services when the power station is not working properly. Local government and the water board decide on the management and flood protection of specific infrastructure facilities, like the food market, the hospital, the power station, and more. But they don’t have enough means to take care of everything.

Just as in the real life, citizens and authorities of the valley have a lot on their minds, even without floods lurking around the corner.

Nobody knows which parcels the flood will strike. Only the water board have the historical data about past floods. There is also the feeling of confidence because the levees are supposed to protect the valley. During the first round of the game, the community members focus on reacting to the danger. They prepare the sandbags in case of a flood, they learn how to perform first aid or evacuate themselves properly. Preparedness-oriented actions are a clear choice at this point, as they don’t take much effort that is needed elsewhere. But is it enough? Then the levee breaks. It is always a moment of shock. “What happened, we were safe behind the levees, how come there is a flood now?”

Then the levee breaks. It is always a moment of shock. “What happened, we were safe behind the levees, how come there is a flood now?”

Remember the oak from the fable?

Levees play the role of the oak here. They are an expensive investment, and they have some advantages – but their strength is limited.

And when they break, not much can stop the water from devastating the area. This effect is even bigger if the people are confident that they are safe because the levees protect them.

After the first round, the losses in the valley are significant, but not critical. There are some flood accidents, resulting in the health decrease of the victims. Some houses and assets are damaged. If the owners don’t repair them immediately, the damage will pile up. It is similar when it comes to the infrastructure. Damaged hospital makes the cost of going to the health clinic much higher.

People of the valley know that there will be next flood, but they don’t know how strong it will be. In the second round, they start to think how they can reduce the risk of damage. The long-term actions, like the house retrofitting or permanent infrastructure protection, become popular among the players. They also discover that it is more efficient for them when they help each other, or when they create joint funds to finance specific actions. This social capital is often neglected in the context of the disaster response, and the role of the cooperation sparked by bonds between the community members is often underestimated.

Social capital is one of the five capitals (5C) represented in the game.

Others include:

- human capital (represented by the investment in education and health),

- physical capital (public infrastructure and private assets),

- financial capital (savings gathered by players, avoiding losing the long-term ability to produce income, also insurance – more about it later),

- and natural capital (using ecosystems and their services for increasing flood resilience – more on it later).

These capitals are complementary and describe the assets that the community consist of. Identifying and using them properly fosters community development and safety. With each flood the community experiences, the need for progressing from reactive actions towards flood resilience becomes clearer.

The third round introduces more advanced actions. The water board can now decide to create the early warning system. It is a huge investment but – when it’s working, and the community members know how to use it – it boosts the effectiveness of other protection measures. Citizens and authorities can buy insurance for their houses, assets, and infrastructure they manage.

They face the dilemma of further community development. Should they spend their budgets to improve their houses and infrastructure?

The question how to link the development and growth with disaster risk management is not easy.

Real-life cases show that new infrastructure or housing is often built on flood-prone areas.

There are many reasons why this can happen. The citizens and authorities may not be aware of the risk. The land may be cheaper than in the safer locations. On the other hand, there is also the dilemma of investing in development when the safety is uncertain.

But does it mean that the community should abandon its development goals? This is a hard choice that players have to face.

The fourth round represents a longer period – 15-25 years. During this round, the citizens and authorities decide on implementing long-term actions. They can relocate from flood-prone areas to the safer ones, they can use the natural capital and reforest the deforested parcels, they can also build a retention polder in the upper course of the river. Then, players experience how these decisions improve their safety in a long run. But they also see the future from the different angles: their level of development, the quality of their life, the effects of education of their children. Combined with the lessons from previous rounds, such “time-compression” allows the players to understand how they can design their future, so their community becomes flood resilient.

In the Flood Resilience Game, the players begin with little knowledge about the real flood vulnerability of their community and the ways of improving their safety.

Throughout the game, they progress from reactive actions (levees, preparedness) towards avoiding risk creation (prospective risk reduction). At the same time, they struggle with everyday problems (making a living, being healthy, taking care of children’s education). The game also recreates interdependencies between the specific members of a community. This way it highlights the need for communication, cooperation, and solidarity between them. All of this helps the players connect what happens in the game with their daily realities. Two-hour gameplay allows them to live through a couple of decades, so they can experience the long-term effects of the decisions that they can make now. In result, they can grasp better the whole concept of flood resilience, and why it is so important.

The game tests in Lima were run with the members of Practical Action organization, and in Jakarta with staff from various NGOs: Red Cross Indonesia, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Mercy Corp, Plan and Concern Worldwide. The testers gave their feedback about the game from their practitioner’s point of view. Right now the game is being refined. The next version will be released soon, and the possibility of a mobile application to allow players to handle more complex dynamics while interacting in the workshop is being explored. Stay updated with the Games4Sustainability blog for further information about the game.

You can read about Flood Resilience Game also on IIASA blog and in our Gamepedia.

Photos courtesy of Adriana Keating and Adam French.

The game was developed by the Centre for Systems Solutions (CRS) in collaboration with Adriana Keating and Adam French from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), with funding from the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance.