Almost 40 years ago, a handful of Nordic countries gathered to rework their curricula to include more creativity, collaboration, and communication — skills that are nowadays considered key to functioning in the contemporary world. And it is paying off. Finish teenagers, for example, produce some of the world’s highest scores in maths, science and reading according to PISA rankings. Graduates from Danish, Swedish or Norwegian schools, meanwhile, are now shaping the global market of music, game-design, and technology innovation (it’s enough to mention that Minecraft, Spotify or Skype were all developed in Scandinavia).

So, how are the values of creativity, collaboration and communication realized in the north?

First of all, Nordic schools welcome everyone. The founder and CEO of Scandinavian Education, Hans Renman, points out that social inclusion, democracy, and equality are taken very seriously in the north, thus the education system outlaws school selection and is publicly funded (also at the university level). In one classroom, there are children from all social backgrounds, which not only ensures equal rights to everyone but also teaches kids that respect, communication and openness are key to a healthy and functional society.

Secondly, creativity and collaboration are valued more than rivalry. Finland, for example, has almost no national tests whatsoever. Education as a competitive race is a non-existent concept. Joint problem-solving activities, collaborative group assignments, self-assessment or peer reviews are used to support and verify students’ progress, and no one, either within or outside the school, demands that it’s done according to a pre-defined schedule.

Foremost, however, the Nordics believe in the “joy of learning.” For example, central to early years education in Finland is fun and free exploration: “We believe children under seven (…) need time to play and be physically active. It’s a time for creativity,” says Tiina Marjoniemi, the head of the Franzenia daycare centre in Finland.

The power of play and active engagement is also appreciated at later stages of education, where blended learning, flipped classroom techniques, gaming and peer-to-peer learning are often introduced to support kids’ natural curiosity and encourage them to be responsible for their own learning.

How can other countries follow the Nordic way and immerse students in playful learning?

To answer this question, I decided to interview the developers of a serious Internet game, New Shores. The game, which has already been mentioned a couple of times on the blog (see here or here), has been developed for a similar purpose: to match the needs of a new, more digitized and more participatory school. How does it fulfil its mission? Is it working? And how can it be accessed and applied by teachers?

Meet Zsuzsa Vastag from the Rogers Foundation for Person-Centred Education (Hungary) and Mária Borvák from TANDEM n.o. (Slovakia) who co-worked with the Centre for Systems Solutions on New Shores – a Game for Democracy.

Tell us something about yourselves – what is your professional background? What do you do?

Zsuzsa: I am a psychologist, and I work now in an NGO called Rogers Foundation for Person-Centred Education, as a trainer and a project manager. We are conducting mostly teacher trainings in Hungary. Our main topics are emotional education and free play and games in schools.

Mária: Currently, I work as a professional leader and senior trainer of TANDEM n.o. We are focused on developing competencies in different areas of people’s lives through experiential learning.

The New Shores game has been developed as part of the Erasmus+ project. Where did the idea for a joint initiative come from?

Mária: All three organizations that are involved in the project, that is, the Centre for Systems Solutions from Poland, TANDEM n.o. from Slovakia and the Rogers Foundation from Hungary, are highly interested in developing new and innovative ways of dealing with topics that are important for our society. So in my mind, there was no question that we should join forces and work on the topic of democracy and active citizenship in a new way.

Who is the main target group(s) of this project? Why did you choose to address the project to them?

Zsuzsa: The primary target group of the project are educators who work with young people (between the ages of 13-30) in youth settings (camps, youth groups, schools, etc.). The secondary target group are the young people themselves – whom we have planned to reach indirectly, through the educators. This way, we hope to create a larger impact in terms of young people becoming more active in their community.

Mária: Just like Zsuzsa said.The overarching goal of the project is to reach young people. To do it, we turn to their leaders – teachers, trainers, tutors. We want to help them understand that in the era of digitization and more participatory educational approaches, their role as a teacher may be different. It may mean moving away from being a mentor or expert to becoming a partner and facilitator, who encourages independent thinking and discussion. Thus we offer free trainings to teachers during which they learn to use the game and the methodology.

What does the subtitle “game for democracy” mean? Why did you decide to raise this topic? And why did you decide to do it by the means of a game?

Mária: We consider the topic of democracy to be utterly important as only active and involved people can form their own path, the path of the society they live in. We believe in participatory functioning, which is the base of a democratic community. We also believe that developing anybody’s competencies can only happen effectively through experiential learning, which is highly enjoyable and offers not only information but an enjoyable way of learning skills and developing attitudes.

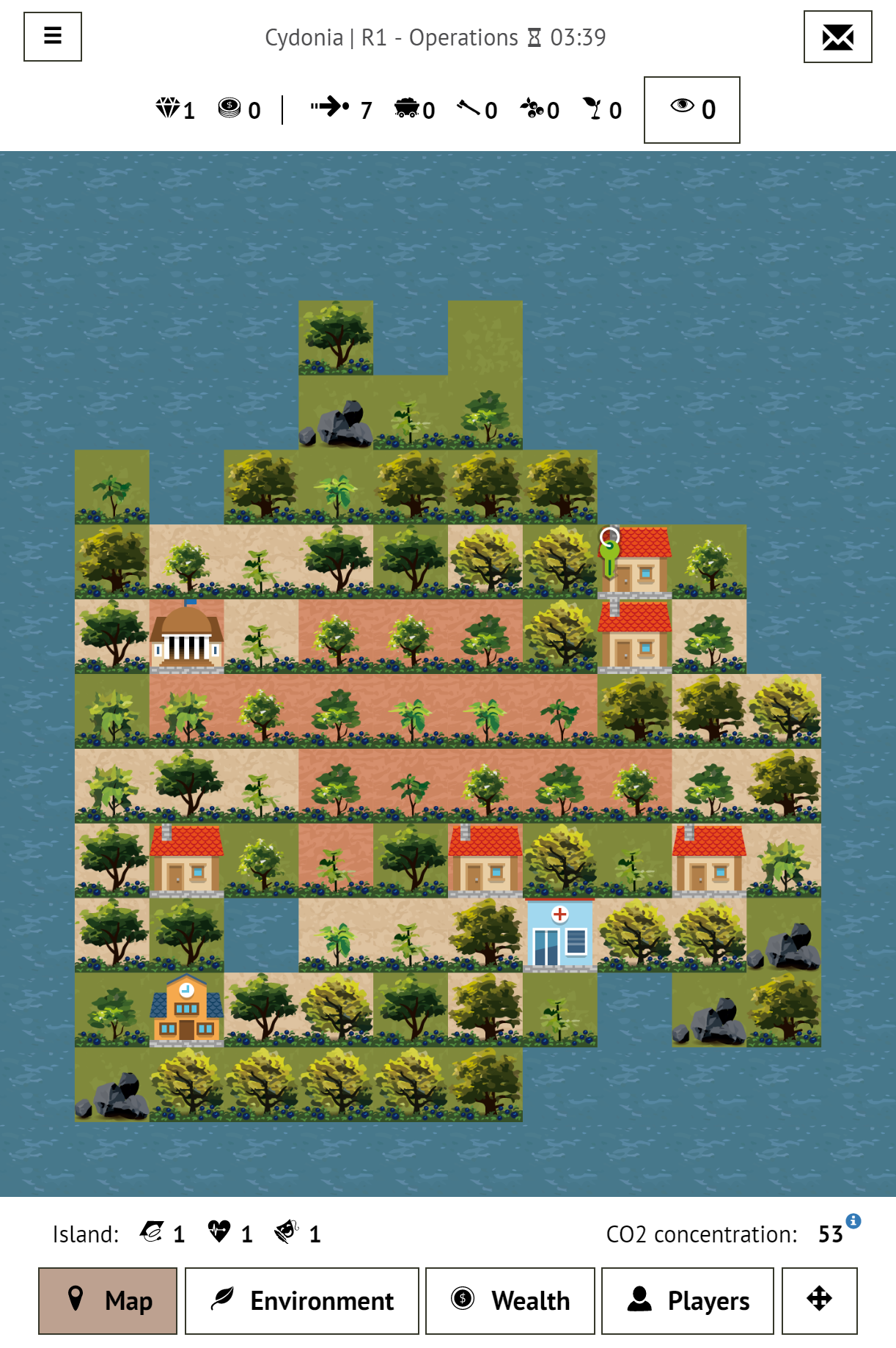

Zsuzsa: It is a game for democracy, as we are developing an online simulation game with a serious aim: letting young people experience what democracy means personally, what it takes to reach common decisions, to let yourself be heard, to take care of others’ needs and opinions while representing your own needs and opinions. We decided to use a game, as we believe that experiences can be the most effective tools to reach real change in attitude, and a game can serve as a fun and, at the same time, meaningful experience.

What is so special about the game-based approach?

Mária: A game is a great way to immerse the youth in doing, not only thinking about a concept.

Zsuzsa: We think using games in education is a great way to connect with young people (and adults as well…), as it is engaging, and people can have real, meaningful experiences through a fun activity. It is way more effective than a lecture about democracy – a game and their own experience makes it personal and therefore a personally more important issue for participants.

How can this tool be used at school, at work?

Zsuzsa: The game itself takes about one and a half hours to play, together with the necessary debriefing afterwards. This is a timeframe that can be relatively easily integrated in traditional schools, as it is the time of a double lesson. But if teachers/educators have more time in their hands, on a project day, at a summer camp, etc., then there are nearly endless opportunities to create a workshop or a series of workshops according to the pedagogical aims of the educator (whether it’s mathematical competence development or attitude shaping towards democracy), by choosing the appropriate follow-up activities.

Mária: What makes it very easy to use is that fact that you only need a good Internet connection and a PC or laptop to access the game; you don’t even have to be in the same location. It is very easy to set the game up, and there are many tools to help make the game not only enjoyable but very easy to learn from.

You mentioned that it is enough to have a good Internet connection to play the game. So how can I access it? Is it free?

Zsuzsa: Yes, access to the game and all additional materials for teachers and players (such as the workshop scenario, a moderator video tutorial or player introductions) are free. To learn how to use them, all you have to do is register to the Edmodo platform, which is a very quick process; you only need an email address, and you are in.

There are four language classes there – English, Polish, Slovak and Hungarian. When you follow the appropriate link, you will find instructions on how to join one or all of them and read, watch or download all materials and become ready to conduct a game with your students. They are neatly divided in 9 different chapters that you can browse through one by one or select only the topic that interests you the most.

The platform is mainly addressed to those educators who are interested in using the game in their work and therefore want to learn about the methodology behind the game, the technical necessities, and the way to build up workshops around the game. It is also a way for them to exchange their experiences, ask questions from each other, create a community. And finally, it is a place to share their students’ achievements as well: If during a workshop they have produced something, the teachers can share it here.

Have you noticed any interesting reactions of players during the games? What are the most important lessons learned?

Zsuzsa: What I like the most is when I see that people are becoming really engaged: They do care a lot about the state of the island in the game, even though they entered the situation as “professional adults” – but within the game, they can be just humans being engaged. Of course, “being engaged” in this sense can also mean negative emotions, possible conflicts – which are good, in terms of real and adequate emotional responses to a situation. The important thing is that we do work with these emotions afterwards. Its is also great to see how insightful people are usually after the game: They do see the connection to real life, and many time, I have seen a “light-bulb” moment, when people connect the way they were behaving in the game to how they behave in real-life situations, or how humanity works in the real world.

Mária: The most satisfying reactions are always the ones where you see that people forget where and who they are because they thoroughly enjoy themselves while playing the game. This also means that they are so involved that afterwards there are heated discussions about how all of this work in real life, and mainly how they personally would react in such a situation. These personal reflections allow us to form their attitudes and teach them skills necessary to participate in their own lives.

Can games replace traditional education?

Zsuzsa: Our aim is not to completely replace traditional education, but to offer an alternative to it, a tool that can make education more colourful, aiming for a more diverse impact. I think it is important that educators have a toolbox they can open any time they want and choose a method that fits their aim well. Traditional education can be also useful, but games can add the personal aspects to the theoretical knowledge.

Mária: Every type and form of education can be beneficial, so in my eyes the more we work with a topic, and the more tools we use, the better the outcome. So I would suggest using this game as an equivalent to traditional methods of education, but also keeping the already-used methods. This would mean a higher exposure of young people to the topic from many different aspects.

What are the next steps in the project?

Zsuzsa: We are in the final phase of the project, and our main agenda at the moment is promotion of the game and the e-learning platform. We would like to reach as many educators as we can, so we can have a large impact.

And what are your plans afterwards? In what direction will you go?

Zsuzsa: We will definitely use the game later on, even after the project ends: We plan to offer workshops to schools and other interested groups of educators. We can also use it personally, as it can be a fun activity with friends and colleagues, as well.

Mária: We are introducing the game and methodology into our own democracy project and incorporate it in an even more essential way so as to reach even more people who can make use of the game itself.

Thank you for this fascinating interview and the best of luck with promoting the game among educators!

Zsuzsa and Mária: Thank you!

What about you? What do you think about game-based learning? Do you know any other methodologies that would follow the Nordic way of education? Or are you a traditionalist, believing in the power of textbooks and lectures? Share your opinion in comments!

How did you like this post? Let us know in the comment section or on our social media!

You can also fill this short survey to help us create better contentent for you!

For more games about democracy, civic society and SDG 16 visit our Blog and Gamepedia!