When faced with the impending disaster of climate change, we can either adopt the policy of an ostrich, a fox, or a lion. An ostrich pretends nothing is happening. A fox only cares for itself and furthers its interests by way of deceit. A lion takes responsibility for the entire animal kingdom and deals with the problem head-on.

This applies both to regular individuals and corporate executives. The difference is that the latter are more powerful and their actions have greater consequences for the world.

Think about the Exxon scandal. Despite its knowledge about the negative effects of their business on the climate, this oil and gas corporation concealed it for the sake of short-term profit. Or about the super-rich bankers who plan to abandon the rest of humanity when climate change hits the hardest. Or the bulk of small companies that dump toxic waste into the environment.

There are positive examples, too. Ørsted, a Danish energy company, has shifted away from coal to renewable energy sources, reducing their carbon emissions by 83%. In the US, IT company Cisco Systems runs its hardware on 99% green energy. And over in Japan, plastics manufacturer Sekisui Chemicals builds environmentally-friendly housing.

As optimistic as they are, these stories are still too far and between. We need fewer ostriches and foxes, and many more lions.

But how do we turn ones into the others? How do we convince those who devoted their entire lives to the pursuit of money that they should be saving the planet instead?

In the present day, it’s not a false opposition. The actions of corporate stakeholders are governed by the short cycle of financial reporting. Anything that needs more time is a lost cause because it’s not designed as profitable. Yet it takes years, and more likely decades, to achieve and maintain sustainability. That’s why it is incompatible with profit in the current economic set-up, where we reward short-term gains and penalize long-term investments.

However, money and economic systems are merely a matter of social contracts. They may have better alternatives. In fact, some currencies have the potential to incentivize far-sighted behavior.

For example, Wellness Tokens were developed to promote chronic disease prevention in health care; Ecocoins are intended to encourage sustainability; and some other alternative currencies in development, such as ScotsPound and BerkShares, aim to improve local economies. These currencies work like conventional money but are regulated to fit specific purposes. You can earn Wellness Tokens through healthy or environmentally-friendly activities, and spend them on certified eco-products; Ecocoins do not bear any interest, are earned by investing against climate change, and can only be used by corporations.

In general, such alternative currencies are thought to be able to affect human behavior in desired ways through a combination of two factors. First, they function like money, which makes them attractive to use. Second, they are governed by a set of rules and limitations meant to favor some actions or disfavor others.

Save the Future is a game that sets out to test alternative currencies as a method for effecting behavior change toward sustainability. The game’s alternative currency includes mechanisms designed to reward long-term, environmentally-friendly business activities, and to inflict penalties for ones that are short-term and harmful. What’s important, the currency is entirely optional. Participants learn about it at some point, but are under no obligation to introduce it. Therefore, at least in theory, they could achieve sustainability with the use of regular money alone.

We had the pleasure to talk with the developers of the game, Timothy Giger and Bartek Naprawa, about its underlying ideas and how they were forged into a digital product.

Could you briefly explain in what context this game was created?

Tim: The game was created as part of the EIT Climate-KIC Long-Termism Deep Demonstration. The overall aim of the Long-Termism project is to investigate how society values time. It focuses on the transformation of mindsets and the establishment of mechanisms to enable shifting towards long-term thinking, which will facilitate sustainable behaviour and investments into sustainability.

The Deep Demonstration process is co-creative and evidence-based, engaging a large multidisciplinary panel of partners working together and sharing ideas. It is in this context that the idea of creating an online Social Simulation as a platform for creative experimentation around systemic levers came together. The simulation will be used as a collaborative tool for testing alternative policies and institutions that can be later combined into a more sustainable and long-term oriented financial system.

What has been your experience of the Deep Demonstration journey while developing this game?

Tim: Working closely with EIT Climate-KIC and Long-Termism partners during this project has been a great experience and taking part in high level discussions around the notion of long-termism has enabled us to create, in my opinion, a much more meaningful simulation. The simulation focuses around the financial sector and the dilemma of long-term decisions vs. short-term solutions, and therefore a deep understanding of the sector was necessary. At the Centre for Systems Solutions, we’re experts at making engaging simulations that revolve around societal challenges, but we often lack in-house expertise on specific topics. This is where being part of such a project is a great opportunity, because we get to collaborate with experts from all types of sectors.

Could you briefly describe what the game is about?

Bartek: The game is about interlinkages between social, financial and environmental systems. About looking for a way out of seemingly hopeless conflict where population must consume, business must grow, and nature must survive. We focus more on the financial aspect here, and test the mechanism of rewards in alternative currencies, for eco-friendly actions of businesses; we analyze how it influences other elements in a very complex system of the simulation.

How did you get the idea of creating the Save the Future?

Bartek: We decided to take parts of our older title (The World’s Future, which had a similar aim and turned out great), and looked for possibilities to further improve on that. We realised what was missing (mainly the aforementioned financial aspects), and which functionalities could be simplified and automatized.

Why did you choose serious games as a medium?

Bartek: Serious games allow us to immediately see the results of our actions, without putting ourselves in positions of risk. They provide a safe environment for experimenting with varying approaches and for taking different paths – as long as the quality of the game warrants replayability and keeps the users engaged. With an adequately designed system, we can experience long-term, global changes in the matter of hours. An integral, extremely important part of every workshop utilizing such a tool, is the debriefing, i.e. space for players to exchange experiences and discuss lessons learned. Of course they also have the possibility of debating their strategies during the game itself.

How did you decide what elements to include in the game?

Bartek: That wasn’t exactly part of my duties; as a graphic designer I usually am less involved in deciding on the content of the game, but rather in putting the content into an appropriate form that will ensure smooth user experience. But I can say that shifting focus of the game towards things like currency exchanges and stock markets was definitely the answer to the needs of the target group.

What was the most important for you when working on the initial design?

Bartek: To be honest, time constraints. The main design decisions were dependent on this. Specifically, deadlines determined how much of the already existing assets we would use. Of course the ideal situation would be to start from scratch every time, but we didn’t have that luxury.

Tell me more about the graphic design.

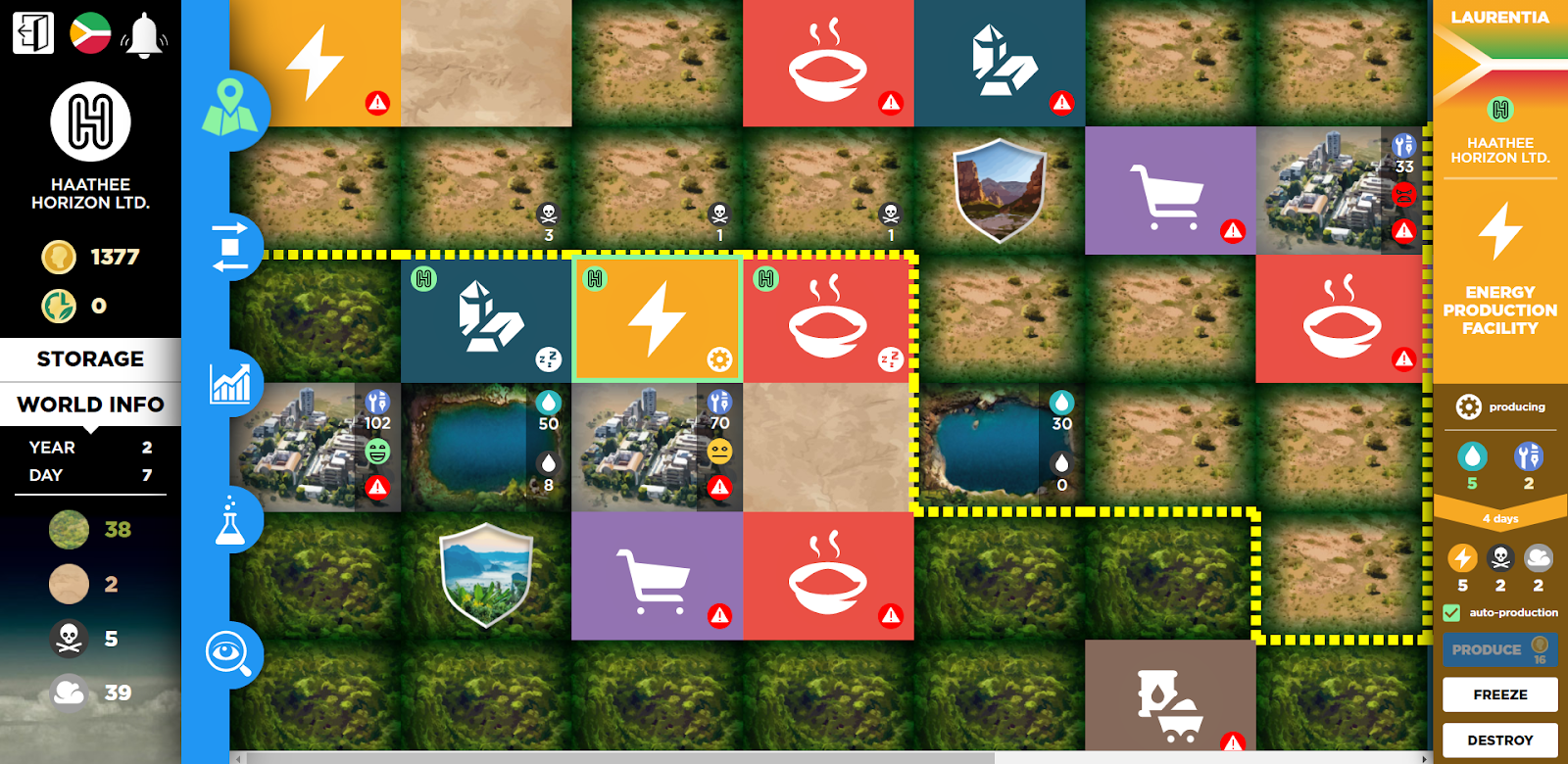

Bartek: It’s a great challenge to design a game this complicated, to be compatible with mobile screens. Usually mobile games are much more straightforward, and here we have tons of elements to show and describe. That’s why we opted for a very simple style, with solid colors, stripped down icons (readable in very small sizes), and unobtrusive text explanations in the form of tooltips and discreet popups. Still, the game requires the moderator’s introduction to be fully understood in the short duration of a workshop. Another important thing to notice is color coding (elements related to each other have the same colors – e.g. a facility producing food, a project increasing food use efficiency, and the food itself as a resource in storage or on the market). On a more general level, I am obsessed with consistency of sizes, margins, stroke widths etc., so quite a lot of time went into making sure that everything is coherent across different windows and panels.

Do you feel a difference between working on game design in pre-covid times and now? Did the current situation influence the design in any way?

Bartek: In this case, not at all. Our programmer works abroad, so we wouldn’t talk face to face anyway. I still use the same hardware and software. The only difference is the room I’m sitting in while working, and the fact that I can play my favourite music out loud without driving the rest of the team crazy.

Who is the game for?

Bartek: Mostly for businesspeople, financiers, and government officials on every level. But everybody benefits from understanding the system’s complexities, and there is never enough awareness-rising out there, so I would say that everyone should play. However, the game is definitely not for kids, due to its high complexity.

Where did the title come from?

Bartek: We live in difficult times and the future is a scary prospect – climate disaster being the main factor responsible. It has (or soon will have) negative impact on every aspect of our lives. We must act now to „save” the future for generations to come. The title is a call to action. In fact, I would add an exclamation mark when I’m thinking about it now. If „saving the future” means fulfilling the populations’ needs while protecting nature and sustaining economic growth, then the game is exactly about that. It throws many challenges at a player, but proves that there is no situation unsolvable, as long as people act together and put the common good before particularistic interests and short-term benefits.

Are there any skills needed to play the game?

Bartek: Just basic familiarity with a tablet, smartphone, or mouse and keyboard. Of course, a person with a strong talent for negotiations or a knack for economic strategy games will surely have higher chances for better personal results, but remember – this is a multiplayer game and no one will save the global future alone. Even a group of the most skilled, smart players wouldn’t keep the system in a sustainable state for long, without willing to cooperate and agree for compromises along the way.

What do you want the players to take from the game?

Bartek: We want them to realize the importance of open communication, of working together as a team, as opposed to pursuing individual goals. I can imagine that in a perfect scenario, players would have a chance to learn from their mistakes and on their second try they’ll achieve a better end-state of the game’s world, even if the first attempt was a complete disaster.

What psychological and social processes may occur in and between players?

Bartek: This is hard to predict, because there are always different people in different groups, and no two sessions will be the same. A sensitive person may experience a strong feeling of loss when his/her long and carefully developed assets are destroyed by natural disasters. Someone would feel empowered after successfully pitching his/her idea to other players, while at the same time other participants can experience frustration because their voices didn’t break through. Feeling lost in a complex, fast-changing system is another common symptom of taking part in our simulations. Hopefully it is caused more by how accurately a given game represents today’s reality, and not by user interface flaws.

What do you think are advantages of game-based learning?

Bartek: Game-based learning is experiential, that’s the main difference from passively listening to a lecture or reading a book. There is clear action and reaction, cause-and-effect relationships become more pronounced. Kids in school always prefer practical exercises over theory, whether it’s making smoke in chemical experiments or growing plants for biology lessons. This applies to adults, too: the more engaged we are in a process, the more we will remember the knowledge gained. Good games can make us forget about the world outside and be 100% „in the moment”. This precious state of flow should be used more often for the good purpose of challenging worldviews, re-shaping mental models, facilitating internal reflections… And less often for inventing new ways of killing zombies (although it’s always fun to kill a few).

Do you think we have to think differently about the future of education now? How does it affect serious gaming?

Bartek: Covid is a temporary thing, but it will have certain lasting effects on gaming as a whole, not only the “serious” variety. I can imagine that nowadays more people than ever are interested in games simply because this is one of the better ways to kill the time when you are locked in at home. The whole industry experiences historical growths. Regarding education: in CRS we don’t make face to face workshops with dozens of attendees anymore, we were forced to focus on online experiences that are way harder from the moderator’s (or educator’s) standpoint. It’s difficult to manage a group when you can’t see people’s facial expressions and when they can’t interact with physical objects like cards and tokens, or with each other. You have to be supportive, but asking „is everything clear, do you need any help?” every 2 minutes can be annoying. The temperature of discussion is definitely lower online, I have the impression that participants in Skype/Zoom environments feel somehow more intimidated. It’s a great challenge to reduce this intimidation and make sure that everyone feels equally welcome, involved, and appreciated.

Can serious games promote sustainability? If yes, how?

Bartek: Yes, they can and they do. Mostly by showing the opposite: the results of unsustainable policies or behaviours. Even if a game doesn’t clearly specify any conditions of winning and losing, it can surely make an unsustainably-acting player’s life much more difficult. Thanks to the compression of time, players can experience the long-term results of their reckless behaviours in the matter of hours – and these results can hit really hard.

How did you like this post? Let us know in the comment section or on our social media! You can also fill this short survey to help us create better contentent for you!

For more games about climate crisis, climate change and SDG 17 visit our Blog and Gamepedia!