In my discussion last year with Games4Sustainability about how the Natural Capital Project (NatCap) uses serious games, one of the things we talked about were the main challenges that we faced while designing our games. Based on some recent experiences NatCap has had with developing and leading our games, I’m returning to take a closer look at how we’ve faced the challenge of translating one of our games, Tradeoff!: Roads to a Resilient Future. We recently had a two-week span during which we played our game on three different continents (Asia, North America, and South America), with three different audiences. While the opportunity to share our game with diverse groups is exciting, it also presented challenges not only for linguistic translation, but for communicating across multiple cultures and experience levels.

NatCap for utilizing natural capital

As a reminder, NatCap is a collaborative project between several academic research hubs (Stanford University, the University of Minnesota, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences) and two environmental NGOs (The Nature Conservancy and World Wildlife Fund). NatCap works to empower governments, NGOs, and companies to incorporate nature’s diverse benefits to people into major decisions around the globe. In the process of sharing and training people on our approach and tools for utilizing natural capital, we’ve been developing training games to enhance and enrich our learners’ ability to take up and absorb these concepts and practices.

Easy ‘Road to a Resilient Future’?

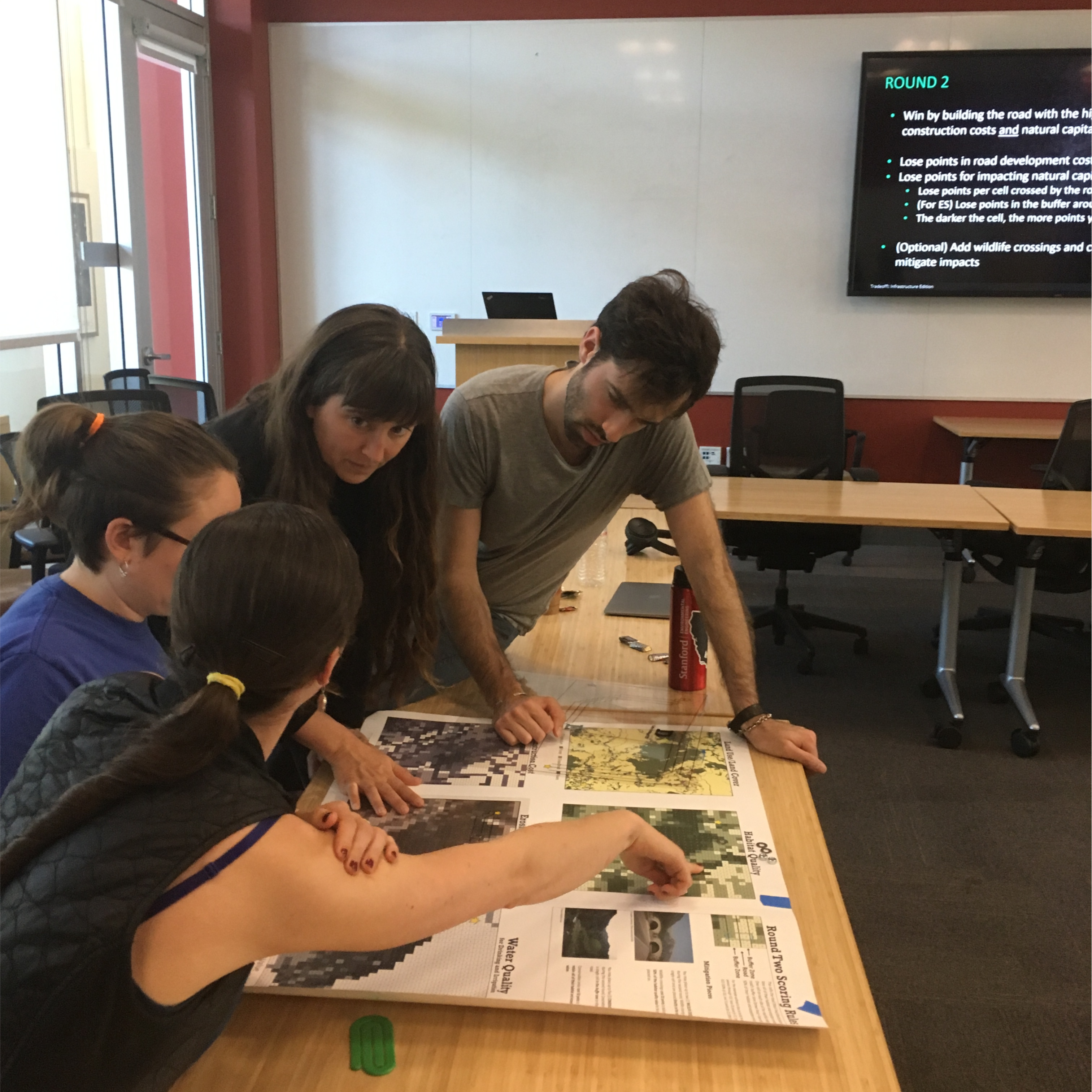

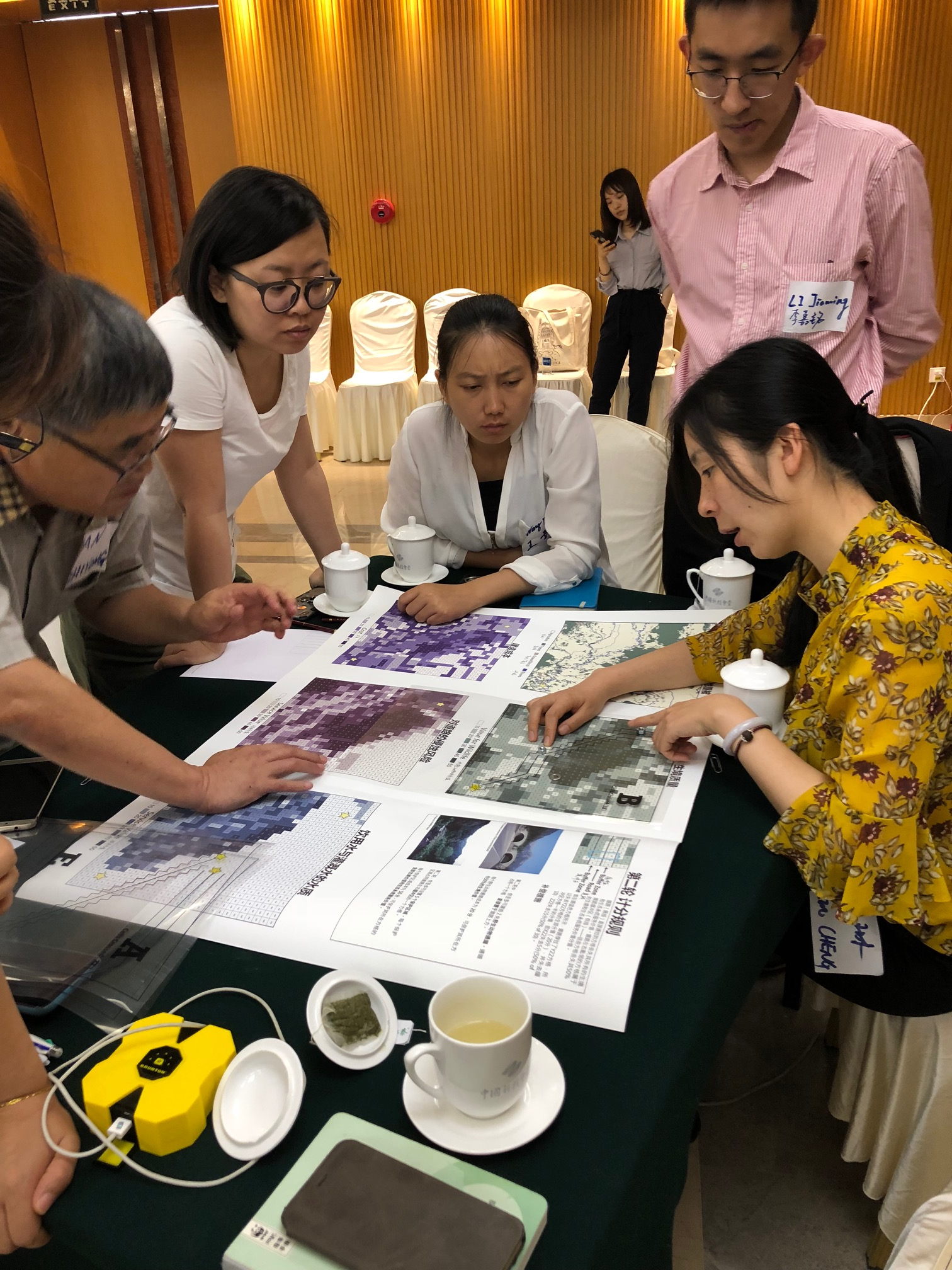

Roads to a Resilient Future is played by multiple teams of four to eight people in two rounds. In the first round, teams are tasked to connect two population centers on a terrestrial landscape. The first round is pretty quick: there are five possible roads to choose from, and players are given two maps to help them choose, one that shows the lay of the land (what we call a “Land Use/Land Cover,” or “LULC” map), and one that shows a coordinate plane of how much it costs to build a stretch of road across any given cell on the map. It’s after the first round that things get a bit more complicated: after having an initial score given to each team’s choice, it is then revealed that natural capital losses due to the construction of the road are also being factored into the scores, and everyone’s score drops precipitously.

Teams are then given additional maps of the area, showing where the values for three services—habitat quality, sediment retention, and water quality—are located. They spend the second round considering this additional information and deciding if they should change their selected route to another one, and whether and where to place protected areas and/or wildlife crossings (which cost extra points but preserve more of nature’s value) along their road as well. The team with the highest score at the end of the second round, or the team with the most improved score from Round 1 to Round 2, wins.

Breaking barriers

This game has a multilingual history. We initially developed it with a team from World Wildlife Fund (WWF), who were using it at a workshop for infrastructure developers in Southeast Asia. As soon as we completed the English-language version of the game, key guidance materials were translated into Vietnamese as well. Our bigger task for translation came up more recently, as we prepared the game to be played in China and Peru. The initial language translation was not so hard (it mostly comes down to having the personnel or resources to do the translating); the challenge was in ensuring that the game itself made sense to these global audiences. Take, for instance, the word “trade-off,” which didn’t have an obvious direct translation into Spanish. Even in English, there seems to be some debate as to whether it should be written with or without a hyphen, and it has specific meanings in several specialized fields. Our audience in Peru were not only Spanish-speaking, but also non-specialist community members, which made things trickier. On top of that, “trade-off” is in the game’s title, so we needed the translation to be short and catchy. At first, our translator couldn’t find a way to both translate the concept of a trade-off and keep the language pithy and engaging. Ultimately, we decided to pull the word “trade-off” from the Spanish-language title entirely, and focus on explaining the concept during gameplay itself. We also had to reconsider our use of the word “resilient,” which also lacked a familiar translation into Spanish. So “Tradeoff!: Roads to a Resilient Future” became “Caminos hacia un futuro sostenible.”

Elephants vs jaguars

Another translation challenge had more to do with geography than language. In the original version, one of the game pieces in the second round are wildlife crossings, which are based on real-life constructions that try to help maintain connectivity between sections of habitat that have been disrupted by a road. In the original version, set in Southeast Asia, crossings were designed for migrating elephants, but we certainly couldn’t expect learners to make decisions about elephants in the Amazon! So, we “translated” elephants to a locally-relevant, but similarly charismatic and wide-ranging species, the jaguar. We didn’t have to change anything in the data for the game, but merely adapt and adjust the storyline.

The last factor that I’d like to mention here is perhaps less about translation, and more about understandability. We are lucky enough at NatCap to reach a wide variety of learners through our games. In Peru, we played the game with local researchers, but also government representatives and community members. Here at Stanford, in the US, we played with a classroom of undergraduate and graduate students in public health. In China, we played with NGO practitioners working primarily in conservation. To reach all those players, we had to develop a game that could be readily adapted to people from a diverse range of educational backgrounds and life experiences.

Reaching out

Our solution to this challenge has been to develop additional modules of learning activities around the game itself. For instance, sometimes it’s necessary to take more time to introduce the concepts of natural capital in-between rounds. The core functionality of the gameplay itself doesn’t change, but the amount of explanation and discussion built into the process now varies widely, depending on the audience. It’s more than just translating the words on the board or in the rules, but also figuring out how to best reach as many people as possible from the same core concepts. Moving forward, we see our games as potential centerpieces of day-long interactive workshops. By translating the whole game experience, we’ve broadened the opportunity for a global community of participants.

How did you like this post? Let us know in the comment section or on our social media!

You can also fill this short survey to help us create better contentent for you!

For more games about Life on land-related issues visit our Blog and Gamepedia!