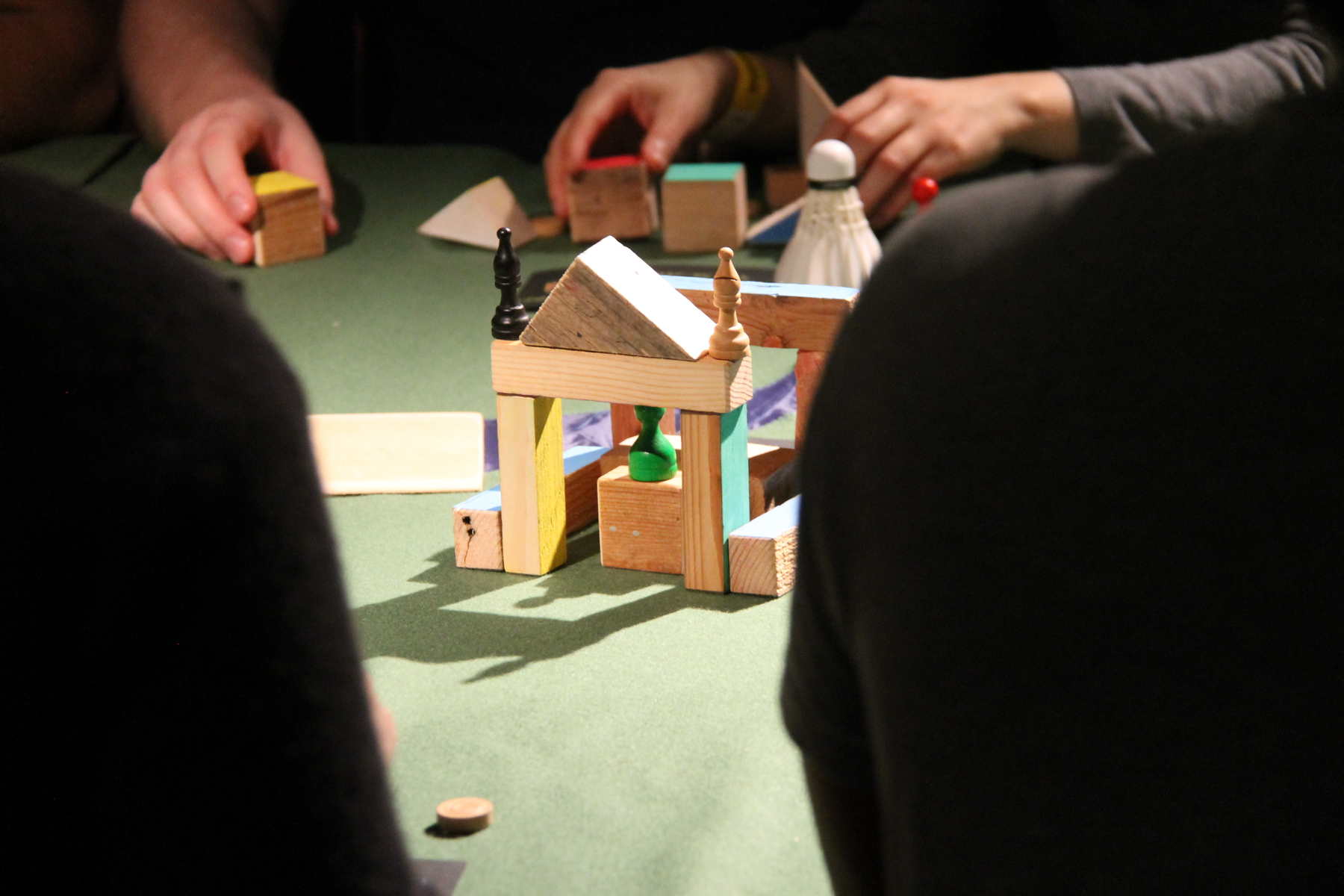

Best Festival Ever: How To Manage a Disaster was quite a unique mix of performance, science and serious gaming. With players working together to plan and manage a music festival, the BFE became an engaging experience for all participants.

The Best Festival Ever was a culmination of 3.5 years of research and development between the UK and Australia. The show explores concepts from Systems Science and Climate Modelling, and already has been used in many venues, including theatres, museums, classrooms and board rooms.

The history of the whole project began in 2006 when Boho Interactive, one of Australia’s leading science-arts ensembles, introduced their audience to the first interactive performance that implemented some elements from Game Theory and Complex Systems Science. Drawing from this experience, Boho – led by David Finningan – created a prototype of the Best Festival Ever show, and the rest is a history.

What was the idea behind the festival and how sustainability fits in all that? We talked with Nikki Kennedy from Boho Interactive.

What sustainability goals can be achieved using serious games?

With BFE we set out to create a game that helped simulate a system to display some of the elements of systems thinking and resilience.

Our aim in regard to sustainability was to create something that allowed a more educated conversation around sustainability – instead of addressing it head on, we attempted to create something that showed what sustainability is reliant upon – a resilient system. In doing so, we have made something that allows our audience to come to their own understanding of why sustainability might be important, why it is currently in a precarious position, and how we can approach making it more realistic.

We have found, from previous experience in interactive theatre, that controversial information is often best realised rather than told implicitly. We also don’t set out to demand that our audience define their stance on climate change or sustainability in the show. Provided an understanding of how systems work and what might make a system more or less resilient is come to then we are content that we have achieved our goal.

What are the challenges for the educator who uses games?

– Creating a game that the players emotionally connect to, something that they can relate to and personalise or feel a sense of ownership over even when the world of the game is ridiculous.

– Explanation of rules, finding a clear explanation of rules for the game that cover the possible outcomes and focus the players on an outcome, while keeping the flow of the presentation or show going/ not losing the players attention or investment in the system

– Identifying the boundaries of the game and the system, and finding a way for the two to correlate – this can be very difficult as natural and real life systems do not naturally fit to boundaries.

– Finding a balance between education and scientific explanation, and maintaining the momentum of game play. Too much science and education, and the games become superficial and demonstrative; too little, and the games have no science to be related back to.

How to provide psychological safety for games participants?

We try to provide psychological safety to our audience through the use of familiar and easily comprehended examples and stories, and the principle of loveliness in the game and participation. We use genre based storylines – simple, familiar, instantly rewarding and gratifying, and give the audience a sense of knowing something – even if they don’t know everything.

The storyline of our show is rooted in the principle of a three act ‘well made play’ form, in terms of at which point the story and the games need to create an introduction, complication, climax, conclusion. We try to work on the principle of ‘loveliness’ (a term lifted from Coney, UK) which refers to giving the audience a lovely experience. We try to do this at all levels, from the way we introduce them to the ways we will ask them to interact and participate in the game, the level of complexity and stress we include in the games and interactions.

To make sure that, while the outcomes of each of our games may not be positive (you have to win or lose a game, mostly), we try to buffer this by giving fun and funny story outcomes to the games. This gives the effect of a reward, even when the audience/players are ‘losing’ the game. We also make sure that while the game can be lost – the festival can be a disaster – the audience do not feel like they are losers, or that they are totally responsible for this. We give the audience some power, but the big and difficult decisions are made as part of the storyline.

The game then is played in response to a series of events that they cannot control. This is not unlike how we individually interact with systems on an everyday basis, we can’t control everything in a system, we can only attempt to manage the parts that we have control over.

What skills are needed to use games for education?

There are skills that are needed for creating the games and then there are skills that are needed for presenting/facilitating the games.

To make games for education, you need skills in observing and comprehending different complex concepts. There is another skill in finding how much of the concept can be explained in order to ensure comprehension at a complex (interesting and not patronisingly simple) but not complicated.

Making the games themselves is a process rather than a skill. Often we use mechanisms from the many games we have played that have some relationship to the concept we are trying to communicate. We then adapt the mechanism and colour it with the example that fits with the rest of the show/games. It is then a process of testing with an audience many many times. We test and retest with various audiences to make sure that what we are doing is accurate scientifically, but also accessible and enjoyable to an audience.

The skills you need for presenting/facilitating the games are being clear and concise, quickly developing and maintaining a relationship with your audience and developing an environment where they’re allowed to play (something that is underrated but very important) whilst also maintaining control and leading the game.

What is the role of game debriefing and how it should be done?

In making Best Festival Ever we imagined the show/game itself as being a communication tool to be used in conjunction with an after game debriefing.

We intended to teach the different terms and concepts in basic systems thinking in order to give audiences confidence in participating in a conversation with a professional systems thinker, scientist, or otherwise.

We found that by giving the audience and scientist (or others) a shared language, the discussion and debrief was richer and the questions more specific. Instead of being caught up in explaining language around concepts that are sometimes difficult to communicate, the conversation could progress further, and explanations about real world research and application could be made.

The debriefing seems to work best when there is some time for reflection on the participation and games. It can start with a short informal presentation by a scientist or someone who applies systems thinking at a professional level that links the games to what they do in the real world. Then he or she allows the participants to ask questions and discuss their experience more freely. There is also the possibility of holding an assisted simple systems modelling session using a pencil and paper diagram around a system familiar to the participants. This kind of debrief is best held in small groups. It helps participants employ some of the concepts they have recently learnt.

What psychological and social processes may happen in and between game participants?

The psychological and social processes that happen in and between game participants roughly mirror the benefits of a participatory systems co-modelling. When participants seek to understand the big picture, observe how elements within systems change over time, and generate patterns and trends, they consequently create an environment where they can test their assumptions. As a result, they are allowed to consider an issue fully and may resist the urge to come to a quick conclusion, taking into account short term, long term and unintended consequences of their actions.

We aim to allow audiences to be presented with the elements of systems thinking and modelling practices. And then allow them to form their own application of this onto systems familiar to them. We don’t seek to change minds but provide a different way of thinking in a fun and engaging environment. Another social process that occurs during these kinds of games is that it becomes difficult to victimise or blame any one party for the collapse or pressure placed on a system.

What are the benefits of games as a method from the trainer’s perspective?

Games are almost always fun. Any teacher will tell you that learning and true comprehension is so much easier and more effective when those that are learning are having fun. Therefore they are very useful in explaining complex or typically dry subject matter. Games provide a way of learning that can (if designed carefully) engage different kinds of learners; those that learn through listening, those that learn through observing, those that learn through talking or discussion and those who learn through doing or having a tactile engagement.

The interview was held in 2015 and was part of the Games for Sustainability publication. For more info on Best Festival Ever: How To Manage a Disaster visit Boho Interactive website! Let us know if you liked this post! Would you like to see more of interviews on our webiste?