About one month ago, on the 8th of October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a new report on “[…] the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways”. In the report, IPCC scientists and researchers assess the current efforts in climate change mitigation, and calculate the costs and benefits of staying with a 1.5°C warming scenario, compared to a 2°C scenario. According to the 91 authors of the report, the benefits of limiting global warming to 1.5°C would be significant, as current warming levels of 1°C have already caused sea-level rise, more heatwaves and hot summers, and for many parts of the world, worse droughts and rainfall extremes. The authors claim that staying within the limits of 1.5°C would decrease the likelihood of an ice-free arctic from once per decade in an 2°C scenario, to once per century. Furthermore, coral reefs would decline by 70-90% instead of >99%.

The report also calls for urgent action, as the limit of 1.5°C will be reached as early as 2030, considering the current levels of commitment to mitigating climate change. Limiting global warming levels would require unprecedented changes in all aspects of society, and they would need to be implemented very rapidly and at a large-scale. From 2016 to 2035, the world would need to invest an average of around US$2.4 trillion for the transition of the industrial, energy, agricultural, residential and transport sectors, representing about 2.5% of the global GDP. Valerie Masson-Delmotte, Co-Chair of Working Group I, said on this topic, “The good news is that some of the kinds of actions that would be needed to limit global warming to 1.5°C are already underway around the world, but they would need to accelerate.”

So how can we accelerate the mitigation of climate change and enhance the levels of commitment to participate in the mission to basically save the world? As you can guess, there is no straightforward solution. Approaching this challenge requires an understanding of the complexity and interconnectedness of the various factors related to climate change, including social, technological and economic ones. We had a unique opportunity to interview Claude Garcia, who is a member of an association of researchers and scholars who design, analyze, develop, and promote scientific research and its applications to understand complex systems: ComMod. For this purpose, they use an approach which they call Companion Modelling. It includes methods and tools such as role-playing games, multi-agents modeling, and social simulations.

Claude, what is “Companion Modelling” and how does it connect to sustainable development?

Companion Modelling is a method to support collective decision making for natural resources management. What we “do” at ComMod is helping stakeholders describe the system they work with. They identify the different components of the system they manage; what they know and what they do not know. They incorporate in this description what others know. This description becomes a model of the system – hence modelling – and this model can be used to explore, explain, negotiate and agree. ComMod assists stakeholders through all the steps, from problem framing to implementation and monitoring – hence companion.

What are main objectives of the ComMod network?

The ComMod association was created to promote the method, and also to share experiences and learn from each other. If we incorporate scientific results in the models, and systematically document the processes we are involved with, there is an element of personal skill – how to conduct constructive meetings, how to foster engagement and participation, how to construct models that are effective and elegant, these elements require that we continuously improve. ComMod is a network of people that believe that better decision making rests on the capacity to listen to and to integrate different perspectives in the decision-making process.

In which topics do the models you develop immerse? Could you give some examples?

The founders of the ComMod approach were working on natural resources management in Europe, particularly in France, and in the tropics. The first case studies were on irrigation management in West Africa. More recently, some of us have tried to scale-up the models. With my colleagues, we have described the Oil Palm supply chain in Cameroon, to help stakeholders understand the root causes of the low productivity of the country, and explore alternative strategies. We have created a model to explore the interactions between logging, mining, and development in the Congo Basin, to help negotiate offsetting schemes and management plans that are valid across countries. We have a model that describes the links between what happens in the trading places of Europe and China, the Brazil domestic market, and the deforestation in Amazon and Brazil. There is nothing that ties our approach to a local scale, to a village, to a valley. We are realizing that it is possible to be bottom-up at the larger scales too.

Let’s take a closer look at one of the models: ReHab. Could you briefly describe what the game is about?

ReHab is the best way I know to help people realize problems of natural resource management are actually problems of managing people about the resources, not the other way round. ReHab stands for Resource / Habitat. Nothing to do with drugs. But it hooks you! In a game of ReHab, participants are either villagers that need to secure their livelihood by harvesting biomass from a landscape or park managers that need to ensure a migratory bird successfully reproduces in the same landscape. All have a minimal prior knowledge of the ecology of the system, and they need to figure out how it works and what to do, under time pressure. A game typically lasts one hour, and we generally invite people to play two sessions – with different scenarios. The first game ends generally quite bad for all players, and then the challenge is to do better in the second one. And after the game, we debrief. This is probably the more important part. Without debriefing, ReHab, as any of our models, would just be a game. Funny, engaging, amusing for a while, but ultimately futile. Through the discussion that follows, participants draw insights on what is collective action, why it is difficult, why trust and good communication matter, what the origins of knowledge are, and how to cope with uncertainty and free riders. The combination of the game and the emotions it conveys, and the insights gained afterwards is very powerful. I still remember when I played it for the first time, and that is 11 years now.

What was the idea behind creating the game? Which issue or issues did you and your team want to address with it?

It begins as a classic “Tragedy of the Commons” thing. You have a limited landscape, the resource will grow if you give it space, and there is enough for everybody’s needs but not for anybody’s greed, as the saying goes. So the players can wisen-up, develop a community management scheme and problem solved. Except the designers introduced an additional layer. There is an additional actor, the park manager, with different objectives, different means, and different knowledge. This creates a completely new situation with asymmetries to identify and address. In a prisoner’s dilemma, or the tragedy of the commons, all players are identical, and only their actions differ. Here, there are differences that create the tension but are also the key to creating win-win solutions. The problem is that I could speak for hours of Rehab, and you would still miss the most important thing: it is an experience. You need to play, to experience the confusion, the frustration, the joy, the anger, the satisfaction.

Is that why you and your team chose a role-playing approach to the game?

We all know why we face the problems we face. We know where the source of climate change lies. We know why biodiversity is being lost. We know these things. Yet, that does not move us to change habits. Knowing something is different from being aware of something – and I struggle here to find the right words. What I describe is akin to being conscious of something, and this experience of consciousness is notoriously difficult to explain, and impossible so far to measure. I cannot convey to you what it feels like being a farmer in Cameroon who struggles to feed his family and provide an education to his kids, while migrants settle in his village and request access to land. I can tell you their story. I could shoot a movie I guess. Instead, I invite you to play. It will not be the real thing, but it is the next best thing. Fight to make ends meet at end of the turn, negotiate with your neighbor, argue with the moneylender, see in dismay how your painstakingly created cocoa plantation is overrun by the players from the other village or watch you crop go waste because you could not rent the truck in time to go to the market. After the game, you will understand the farmer and his decisions.

Is there a main target group of the game? If yes, who and why?

It differs with every game. Often we design the games to address a specific issue, and the target is, therefore, the stakeholders affected by this issue. It is possible to distinguish three different target groups.

- The first ones are the people that know the system, either because they live in it or because they have studied it. They are the ones that build the model with us.

- The second group is the people that take decisions about that system. It could be the farmers themselves if we are on a local decision level. Or it could be CEO and Ministers in the capital. They are invited to play the game, rather than design it. And through the play, they will understand it better and then design better policies.

- Finally, the third group is made up of everybody who wants to understand that system better. We can always use the model to then teach others about that particular issue.

We addressed these three groups with our work in the OPAL project, with the CoPalCam game. We designed it with the oil palm producers in Cameroon and then used it with the Interministerial Committee for the Regulation of the Oil Palm Sector in that country. And now, we bring it to the classrooms in French and Swiss high schools to teach high school students what is sustainable development and how to achieve it – with the example of the oil palm production in Cameroon.

ReHab is different because it is more generic. As such, there is no more group 1 or 2. But everybody interested in natural resources management can benefit from it, so group 3 is really all of us, irrespective of our level of education and background.

Are there any specific skills needed to play ReHab?

No. You do not even need to know how to read or write. We have designed versions where you play with your body – physically collecting the resources in the game board. We actually make it a point not to explain everything before we start playing. The impression of feeling blindfolded and the need to discover things by yourself are part of the experience.

What are the most important lessons that players learn from playing the game? Which skills may they develop?

They learn it is not enough to bring people to the table to solve a problem. They learn that a bad negotiation can be worse than no communication at all. This already is an eye-opener. They learn collective action is costly and difficult, but that these costs need to be paid to achieve win-win solutions. They learn about the differences between listening and talking. They learn that knowing everything about a system is not a prerequisite for effective action, and that building trust and agreement with stakeholders is the first step to develop adaptive management. They learn so many things! They see the value of data and information, they see why monitoring matters and why enforcement is a necessity. They learn to share their knowledge and recognize the limits of what they don’t know. But maybe, more importantly, they learn to take responsibility. If they fail, they cannot blame it on anybody else.

Which sustainability goals can be achieved by using ReHab?

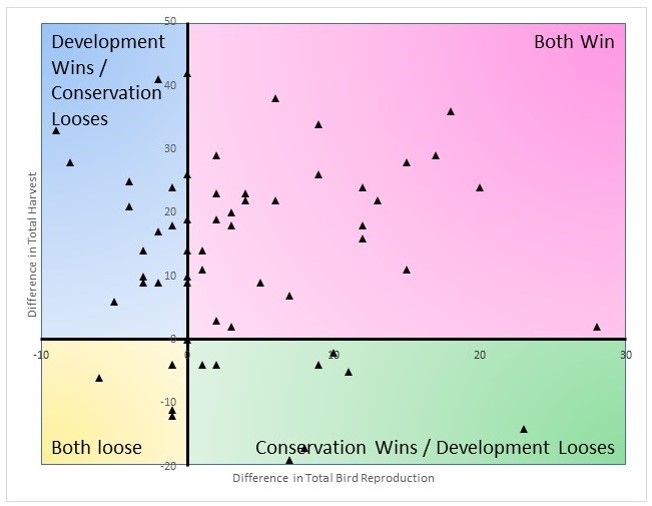

In essence, the outcomes of a ReHab session can be read in two dimensions. One is the number of birds that reproduced in the landscape. It is a measure of conservation success. The second one is the amount of biomass harvested. It is a measure of development success. The core of the game resolves about how will the players achieve these two. Will one side win over the other, in a win-lose scenario, or will they manage to find innovative solutions – the mythic win-win outcome. Unless they go down in conflict and end in a lose-lose scenario. And then we analyze the sessions and draw lessons. So, per se, a game session will not achieve anything directly. But the people will have changed through the process and they will see things differently and do things differently afterwards – and that is the goal we seek to achieve. Changing people’s’ mind.

What psychological and social processes may happen in and between players?

I already mentioned the emotions one feels when playing. They are both positive and negative. Joy, triumph, frustration, anger, arousal, confusion, satisfaction, players reports having experienced all of these. The social interactions are also varied. Alliances are formed and broken, trust is created and lost, authority is vested and removed, leadership emerges and dissolves. Peer pressure, collective action, the emergence of tenure rights, trials, and investigations, conflicts, and agreements, free-riding and solidarity, are only some of the processes that can happen in the two hours that the game lasts. I never tire of watching a game unfold.

In which settings has ReHab been played? Which results could be observed?

We have played ReHab in a variety of settings. We bring the game to schools and universities, from different backgrounds. The lessons are of interest for the environmental curriculum, but also for management schools, economists and the humanities. We have used to explain “why games” to colleagues in research projects all over the planet, at workshop and conferences. We have also used it in the field – in Madagascar, Colombia, India – whenever we want people to understand why we invite them to develop a game to resolve their issue. The game is generic enough that a forester will relate it to his forest concession, a hunter will think it is about hunting and the competition with the other hunters, a fisherman that is about fisheries management. And in a sense, they are all right – ReHab is about managing people about a natural resource.

When you ask about the results of the game, I assume you mean what happened after the game once people had returned to their daily life. I cannot answer that question. I only have anecdotal evidence. The idea for the CoPalCam game was laid out on paper by Patrice Levang, the principal scientist doing research on the supply chain in Cameroon, at the airport on the way back from the workshop where he played ReHab for the first time. One year later we were playing it with the government and decision makers in the panel. I can also tell you, for example, I changed the direction of my entire research after the ReHab game session I played 11 years ago. So in a sense, everything I have achieved since is an outcome of the ReHab game. But I do not think reviewers would accept that as a measure of impact, right?

Did your work on the models and games change your perspective on challenges connected to sustainable development? If yes, how?

Yes. Profoundly. I understand people are not irrational. I understand they take decisions based on what they know but also of what they can, or more precisely, what they think they can. I know that policies that do not consider this will not be successful. I have learned we deal with wicked problems, and that trying to tame them, imposing our solutions on others to problems we alone have defined is a dead end. I have learned to recognize complexity and deal with it. I have learned the best-laid plans go waste, and it is best to embrace uncertainty and cope with surprises. Sometimes they are good!

More importantly, I have learned to question my assumptions. How do I know my values are the right ones? How do I know what to do and what entitles me to give recommendations?

And I understand the world through the models. In ComMod we often use multi-agent systems as a model architecture. For me, this is how I analyze a landscape. I seek the components, the resources, the actors and their desires, beliefs, and intentions. The models are the lenses through which I give meaning to the complexity of the world surrounding us.

How did you like this post? Let us know in the comment section or on our social media!

You can also fill this short survey to help us create better content for you!

For more posts about sustainable development visit our Blog and Gamepedia!